A frame narrative is a literary structure in which one story encloses another. The outer story provides context, perspective, or thematic framing for one or more inner stories. This device can take many forms, from a brief prologue that sets up a tale to an elaborate structure in which the framing account recurs between each embedded narrative. Its power lies in the way it influences interpretation, controls pacing, and establishes a relationship between different layers of storytelling.

Defining the Concept: What is a frame story?

In literary terms, a frame story is the outer narrative that sets the stage for the main tale. It can be a narrator recounting events to an audience, a discovered manuscript, or a conversation that introduces a sequence of recollections. The frame is not just an ornamental part of the story but creates a deliberate lens through which the enclosed story is viewed.

In some works, the frame persists throughout, returning at intervals to remind the audience of its presence. In others, it appears only at the beginning and end, acting as a bracket that contains the primary action.

Purposes and Functions of Frame Narrative

- Contextualizing the main story: The frame can supply background information, establish mood, or offer commentary that governs how the inner story is received. It may situate the tale within a specific time, place, or moral viewpoint.

- Structuring multiple tales: In works containing several stories, the frame provides a unifying device. It offers coherence to otherwise independent narratives, making the whole more than a collection of unrelated episodes.

- Manipulating perspective: By placing one narrative inside another, authors can draw attention to the act of storytelling. The frame narrator may be unreliable, partial, or contradictory, which can cause the audience to question the truth of the embedded accounts.

Classic Frame Story Examples

- Geoffrey Chaucer’s The Canterbury Tales (late 14th century): The pilgrimage to Canterbury forms the frame, while the tales told by each pilgrim comprise the inner narratives. The structure makes room for a variety of genres and voices, unified by the journey.

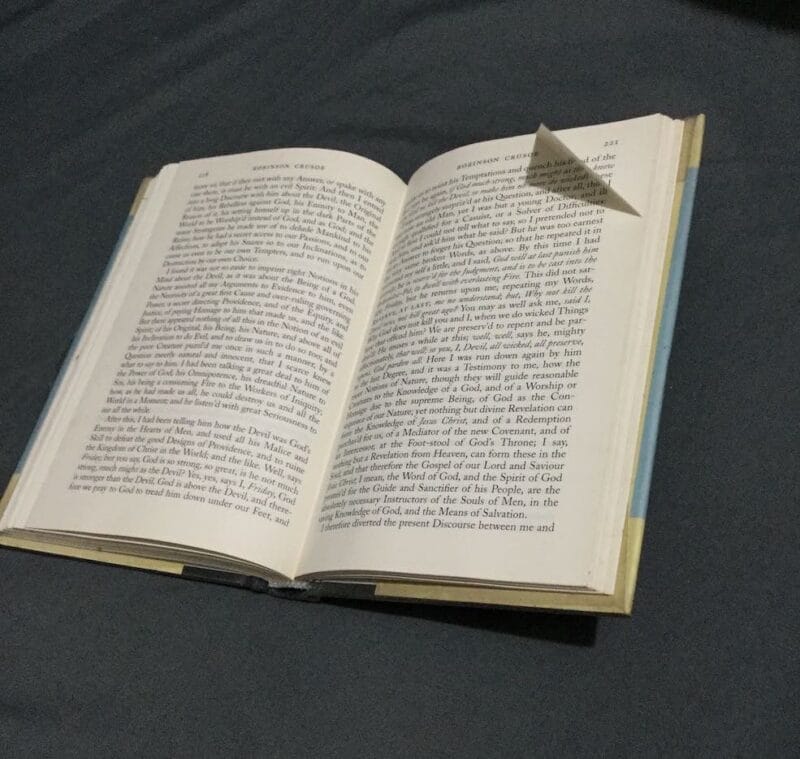

- Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein (1818): The novel begins and ends with Robert Walton’s letters to his sister, enclosing Victor Frankenstein’s account of his life and the creature’s own testimony. The layered frames create shifting sympathies and moral tensions.

- Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness (1899): The novella’s outer frame is an unnamed narrator listening to Marlow’s story aboard a ship on the Thames. This distance complicates the transmission of events, making the story as much about narration as about the journey.

Variations in Frame Narrative Technique

- Single frame with embedded story: A straightforward frame opens and closes the work. The inner narrative dominates, but the frame controls its entry and exit, as in Kate Chopin’s The Awakening (1899), where brief contextual passages heighten thematic focus.

- Intermittent frame revisited between stories: Some works return to the frame regularly, as in Giovanni Boccaccio’s The Decameron (1353), where a group of young people sheltering from the plague take turns telling stories over ten days.

- Nested narratives: In certain texts, multiple frames enclose each other, producing a complex structure. This creates a hall-of-mirrors effect in which each narrator refracts the events differently.

Crafting a Frame Narrative in Writing

To create a frame narrative that works, the writer must decide whether the frame is an active participant in the storytelling or a subtle backdrop. A strong frame has its own integrity: the narrator, setting, and circumstances of the framing account should feel as purposeful as the stories it contains.

The transition between frame and inner story should be seamless yet noticeable enough to maintain awareness of both layers. The interplay between them can invoke comparison, highlight themes, and lend resonance to the work as a whole.

Frame Narrative and Mise en Abyme

While a frame narrative encloses one or more stories within an outer account, mise en abyme involves the mirroring of a work within itself, often through a smaller story that reflects the themes or structure of the larger one. The two can overlap when the embedded narrative in a frame closely parallels or comments on the outer frame’s events. For instance, a tale told by a character in the outer story might echo that character’s own circumstances, creating a self-reflective loop. However, a frame narrative does not require such mirroring, and mise en abyme can also appear in works without a framing structure.

A striking example appears in Emily Brontë’s Wuthering Heights (1847). The outer frame is Mr. Lockwood’s account of his time at Thrushcross Grange, within which Nelly Dean narrates the intertwined histories of the Earnshaw and Linton families. Inside Nelly’s account are moments such as Catherine’s recollections of her youth that echo and refract the tensions, obsessions, and entrapments present in the broader story. Here, the nested narratives both frame the main action and create a mise en abyme effect, as inner events reflect the outer ones in theme and emotional tenor.

The Literary Significance of the Frame

The frame narrative is not simply a packaging device. It can blur boundaries between fact and fiction within the text, lend voice to multiple perspectives, and comment on the nature of storytelling. By controlling the distance between the narrator and events, it molds tone, the perceived trustworthiness of the account, and thematic focus. When used with intention, it becomes an essential part of the literary architecture, guiding how the work is experienced and interpreted.

Further Reading

Frame story on Wikipedia

Story within a story on Wikipedia

The Frame by Decameron Web