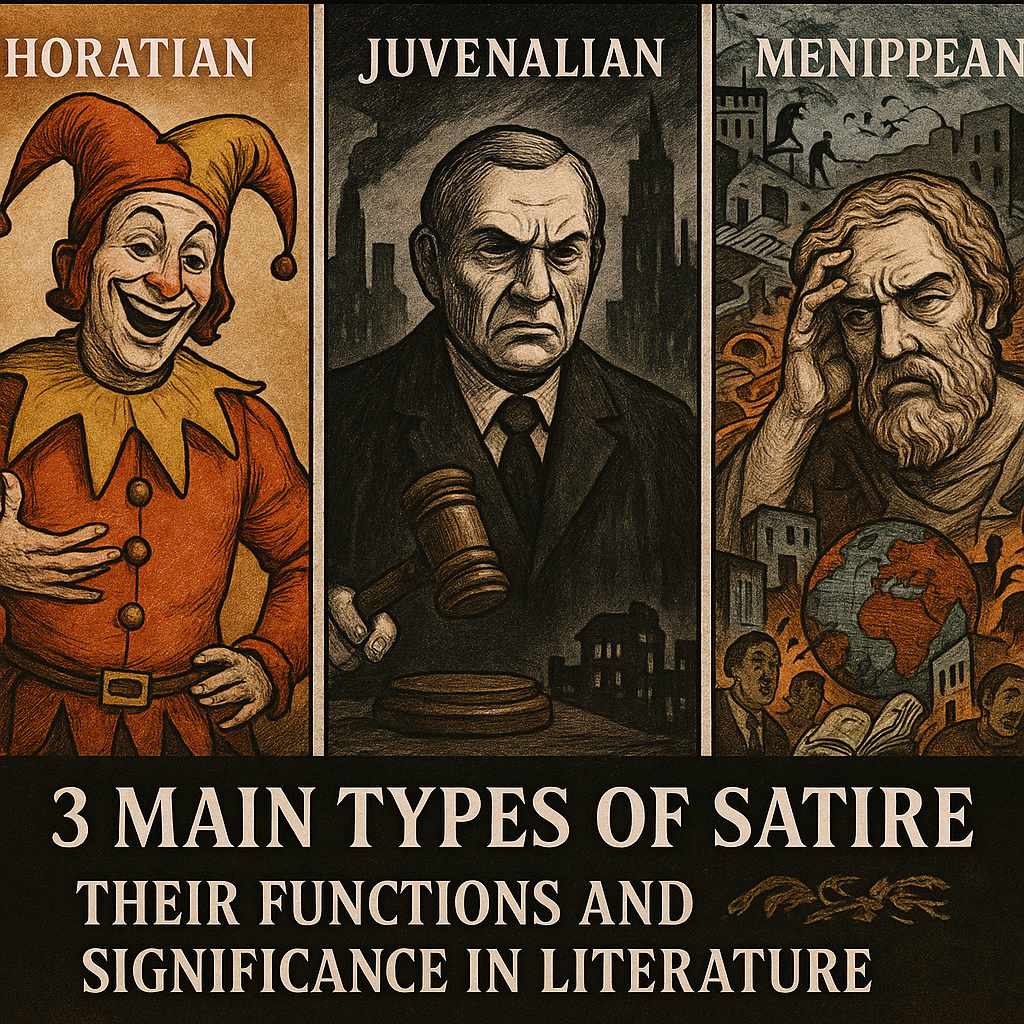

Satire is a fundamental and long-standing mode of literary expression. This mode critiques authority, exposes absurdities, and questions the social order. Far from mere ridicule, satire operates as a mode of commentary that blends wit with moral urgency. To understand satire in literature, one must recognize the three principal types: Horatian satire, Juvenalian satire, and Menippean satire. Each employs its own form of irony, mockery, or philosophical critique, and together they chart the breadth of satirical expression across history.

What is Satire, and How Does it Differ from Irony?

Satire’s purpose extends beyond entertainment by aiming to provoke reflection on behavior, politics, or belief. It flourishes when ridicule is combined with judgment and turns laughter into a tool of commentary.

It is important to distinguish satire from irony. Irony is a rhetorical device in which the intended meaning contrasts with the literal statement. A single ironic remark may exist without satirical intent. Satire, however, builds upon irony and other devices to construct a broader critique of people, institutions, or ideas. Irony can serve as a technique, while satire functions as the larger framework for literary commentary.

The Role of Satire in Literature

Before considering the three types, it is necessary to understand why satire holds such a prominent place in literary history. Writers turn to satire when exaggerating folly, corrupt habits, or rigid dogma, because it disturbs complacency. Its purpose ranges from playful correction to fierce denunciation, always tethered to questions of ethics, politics, or belief. From ancient Rome to contemporary novels, satire functions as a tool for reflection through laughter, discomfort, or shock.

Horatian Satire: Gentle Mockery and Comic Correction

Named after the Roman poet Horace, Horatian satire embodies the most genial form. It seeks to amuse rather than outrage, to laugh audiences into recognition of their own weaknesses. Its tone is indulgent, tolerant of flaws, yet pointed enough to expose contradiction.

Characteristics of Horatian Satire

- Light irony that nudges rather than wounds

- Wit aimed at cultural quirks or vanity

- Use of humor as corrective, not condemnation

Examples of Horatian Satire in Literature

Alexander Pope’s The Rape of the Lock (1712) exemplifies Horatian satire in its playful treatment of aristocratic frivolities. By inflating a trivial social dispute into epic grandeur, Pope exposes vanity without bitterness. Similarly, Jane Austen’s Northanger Abbey (1817) satirizes Gothic fiction with affectionate parody while encouraging discernment without malice.

Juvenalian Satire: Harsh Critique and Moral Outrage

In contrast, Juvenalian satire (named after the Roman poet Juvenal) operates with indignation. It aims for condemnation of vice, corruption, and abuse of position, rather than lighthearted laughter. Its tone is biting, even caustic, and it brings satire into the territory of political critique.

Characteristics of Juvenalian Satire

- Harsh irony and cutting sarcasm

- Moral seriousness directed at injustice

- Willingness to shock or provoke anger

Examples of Juvenalian Satire in Literature

Jonathan Swift’s A Modest Proposal (1729) embodies Juvenalian satire at its most scathing. By “proposing” that impoverished Irish children be eaten, Swift lashes out at English exploitation with bitter irony. George Orwell’s Animal Farm (1945) also falls under Juvenalian satire, its allegorical critique of totalitarianism unsparing in its exposure of political betrayal and manipulation.

Menippean Satire: Philosophical Critique and Intellectual Play

Less familiar but equally important is Menippean satire, tracing back to the Greek Cynic philosopher Menippus. Unlike Horatian or Juvenalian satire, it targets not individuals or institutions but mental attitudes, belief systems, and intellectual postures. Menippean satire often blends prose and verse, shifts tone abruptly, and thrives on digression.

Characteristics of Menippean Satire

- Attack on abstract ideas, dogmas, or intellectual fashions

- Use of parody, dialogue, and fragmented structure

- Preference for philosophical play over moral scorn

Examples of Menippean Satire in Literature

François Rabelais’ Gargantua and Pantagruel (1532–1564) illustrates Menippean satire through its exuberant ridicule of scholastic pedantry and rigid moralism. Later, Fyodor Dostoevsky’s The Brothers Karamazov (1880) incorporates Menippean elements in its polyphonic structure, where competing voices and ideologies collide in satirical tension. In the modern era, Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World (1932) reflects the Menippean spirit in its examination of a society governed by reductive philosophies of pleasure and control.

Functions and Significance of the Types of Satire

Each type of satire serves distinct literary functions. Horatian satire disarms through laughter, appealing to goodwill and reason. Juvenalian satire confronts power with moral urgency, forcing recognition of abuses that polite wit cannot resolve. Menippean satire destabilizes dogma and intellectual complacency, questioning the very foundations of thought. Together, they illustrate how satire in literature is not merely ornamental but vital—an instrument of critique, renewal, and imaginative freedom.

Why the Distinction Matters

Understanding the types of satire enables deeper appreciation of how writers harness irony and exaggeration for different purposes. Horace, Juvenal, and Menippus provide archetypes, but subsequent authors adapt these modes to their own contexts. Whether through Pope’s comic restraint, Swift’s corrosive rage, or Dostoevsky’s philosophical dissonance, satire remains a versatile form. Recognizing its varieties clarifies not only literary history but also the ongoing dialogue between art and society.

Further Reading

Satire on Wikipedia

Horatian satire on Britannica

Juvenalian satire on Britannica

Menippean satire on Britannica